This is a re-post of an entry from ten years ago.

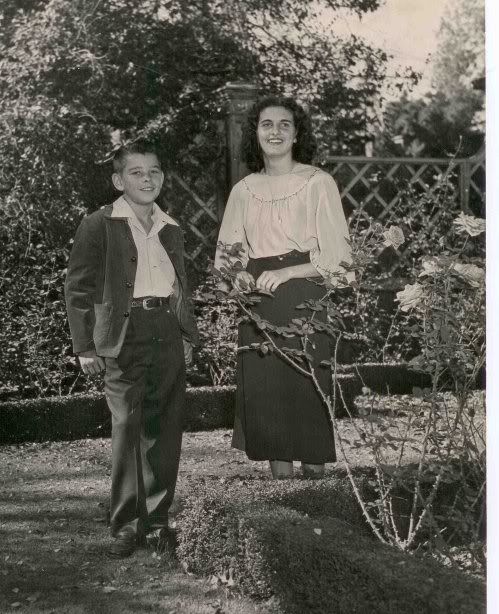

My father would be 85 years old today. The photo below was taken when he was 52 years old. Hard living aged him far beyond his calendar years.

My father would be 85 years old today. The photo below was taken when he was 52 years old. Hard living aged him far beyond his calendar years.

If I weren’t agnostic, I suppose I could lay a lot of blame on Exodus 20:5.

So much of this trip is about finally getting to see Alaska. But I’m self-aware enough to recognize that it’s also about answering that primal urge all men get to simply get away and (at least temporarily) shed our responsibilities. I think all men get this urge. It’s part of who we are. How we handle it is part of what we are. My father had it in the worst of ways and I clearly have it now. It’s different for me however because I know that I know I’m going back home. Read on and maybe this will make sense.

My father died 22 years ago this week. He was 53 years old. His death certificate listed the cause as “complications from Parkinson’s Disease.” But, the reality is even the most highly functional of alcoholic, workaholic chain smokers can’t outrun the legacy of a lifetime of hard living, hard liquor, and unfiltered Lucky Strike cigarettes.

|

| Short, but Most Popular High School Junior Year |

|

I remember walking through Love Field Airport one day with my father, my mom, and my two sisters. I was so taken with the hustle and bustle and all the sites an airport offers a young boy that I barely noticed the tears streaming down both my sisters' faces as we walked. I remember being transfixed on a big Braniff airliner that was parked outside the terminal window where we were waiting when my father hugged us all, said goodbye, and walked through the door; appearing outside on the tarmac shortly thereafter. I recall my mom saying "wave goodbye to daddy." as he climbed the stairs and boarded the jet. I also recall wondering where he was going and why as I suddenly joined my sisters' tear fest. I was five years old.

That trip to Thailand was the first in a long career of multi-year expatriate travel on which my father would embark throughout his career at E-Systems. Over the years, he would write and occasionally call. But phone calls from a war zone across the globe were a tall order in the 1960’s. He always mailed birthday and Christmas gifts to us at home from wherever in the world he happened to be.

My father came back to the States a few times as I was growing up - for what seemed like short visits. One time he and my mother re-married, which was odd to me because I don’t remember ever being told they were divorced in the first place. After two marriages and two divorces (these were to my mother; but there were others), my father moved to Europe for E-Systems and lived in Greece, France, and Germany before returning home for good during my high school senior year. Our relationship was cordial. He was busy. I was busy.

My mom and I had several deep and revealing conversations before she died. Despite all she went through alone, she was concerned that I would hate my father for “abandoning” us. Truth is, I never felt abandoned. My mom loved and supported my sisters and I in ways my father never could (or would) have. As an adult, I recognize her sense of abandonment because she was left to raise three kids on her own. I learned later that she accomplished this with little to no financial support from my father. Still, many times over the years, she would say to me “no one in this world loves you more than your father.”

Not only did I never feel abandoned, I never hated my father. After all, hate is too powerful an emotion to waste on someone you don’t know. There were times when I didn’t particularly like him and wondered aloud just who the hell he thought he was to try to enforce fatherly discipline upon me as a teenager, when in my mind he had not earned the right to do so.

In 1984 at the age of 48, my father was diagnosed with cardiopulmonary stress syndrome. His doctor told him that unless he had a heart/lung transplant soon, he probably wouldn’t live to see 50. By this point, he had accepted an executive position at E-Systems and was living minutes from where I grew up. I was in the Air Force, stationed in Austin, was married, and had two sons of my own by then. I remember him telling me he decided not to have the surgeries. I also remember not being the least bit surprised or, strangely enough, even saddened by his decision.

In 1989, upon being notified his condition had taken a turn for the worst, and that this was probably it, I headed home to Dallas from Austin for the first time in almost three years. On his last day, as I literally carried him to and from the toilet, his frail body twitching uncontrollably and him barely lucid from the effects of advanced Parkinson’s, I remember thinking to myself “I will never put my sons through this.” He beat the doctor’s prediction by three years and he died, just as he lived, on his terms.

Despite his being gone most of my life, I’m pretty sure I loved my father because I still feel a strange sense of loss (or maybe just a void) 22 years after his passing. In a sense, he made me the father and dad that I am to my sons. During my Air Force years, I was faced with a similar career choice that my father had himself faced 30 years earlier. I was offered an opportunity to get involved with a clandestine field intelligence element within the Air Force; a career path that would have me globe trotting year round. It was at this time I had an epiphany of sorts that not only helped me arrive at the right decision, but helped me reconcile how I truly felt about my father. He grew up in a home with both parents and never knew what it was like to not have a dad there. It was easy for him to choose career over family because he had no clue what the ramifications to others would be for doing so. I had the foresight of knowing what effect the career decision I faced would have on my sons - and I chose accordingly. I like to think my father gave me some of his intelligence, but the willingness and insight to be not just a father, but to be a dad is something I know he gave me.

When I look at my sons and contemplate the men they’ve grown to be I quietly, yet proudly acknowledge that there are no cats in their cradles. If I’ve done my job right, the feline population in their kids’ cradles should be nonexistent as well.

I win, Exodus; at least where the cat and cradle are concerned.